Abstract

A noise exposure survey was conducted to evaluate the risk of hearing loss among teachers and students in a specialized music program. The study aimed to assess noise levels and duration of exposure during music practice in classrooms, involving three teachers and forty students. Noise measurements were taken in the classrooms using calibrated equipment, and the duration of exposure was monitored for each participant. Students were also surveyed about their use of personal listening devices outside the classroom.

The findings revealed that noise levels in the classrooms exceeded the recommended LAeq 85 dB(A) threshold for all teachers, and were similarly high for students, particularly those practicing in the smaller classrooms. The survey also found that a significant number of students used personal listening devices at unsafe volume levels outside of class, further contributing to their overall noise exposure.

The report provides recommendations to mitigate noise exposure, including the implementation of a hearing conservation program to reduce the risk of noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). Recommendations involve the use of hearing protection in classrooms, the establishment of an educational program on safe listening practices for students, and regular follow-up occupational noise assessments. Given the identified high-risk exposure levels, it is crucial that both teachers and students adopt protective strategies to safeguard their long-term hearing health.

Introduction

This study aimed to assess the noise exposure levels of public school music teachers and students in order to evaluate the potential risk of noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). Music education environments are often characterized by high noise levels due to the use of various musical instruments, amplification systems, and group activities. Prolonged exposure to such noise can result in NIHL, which is a significant concern for both music educators and students.

The focus of this report is on assessing the noise exposure levels experienced by both teachers and students within the context of a specialized music program. Teachers are considered to be at higher risk of NIHL due to their extended exposure during music lessons and rehearsals. Students, while also exposed to elevated noise levels, typically experience shorter durations of exposure compared to teachers. However, these findings suggest that students may still be at risk, especially those who use personal listening devices at unsafe volume levels outside of class.

Despite existing literature on the noise exposure of musicians, there is limited research regarding the specific risk to music educators, particularly in Australian school settings. Some studies, such as those conducted internationally, have pointed to potential hearing risks for music teachers (Behar et al., 2004, Maffei et al., 2011), but further investigation is needed to provide comprehensive data on the noise exposure of music teachers in Australian schools.

This study focused on measuring noise exposure during specific music-related activities, such as band rehearsals or music theory lessons. The study considered factors such as the physical characteristics of each classroom (e.g., acoustics), the duration of each activity, and the number of students involved. By analysing the average noise exposure associated with specific activities and factoring in the duration of those activities over the course of a typical day or week, we were able to estimate the overall noise exposure for teachers and students.

The study also aimed to assess students’ noise exposure outside the classroom, particularly related to the use of personal listening devices or attendance at live music events.

This report aims to address that gap by evaluating the current noise levels in classrooms and considering the associated risks to hearing health.

Methodology

Noise exposure measurements were taken in two classrooms during music lessons, as well as ‘break out rooms’ with a focus on both the teachers and students. Additionally, the duration of exposure was recorded for each participant to determine how long they were subjected to elevated noise levels.

- Classroom 1: Large Classroom: General teaching and group practice sessions with up to 40 students.

- Classroom 2: Smaller classroom: Small band practice with the use of drums and electric guitars, creating higher noise levels.

- Break out rooms: small group practice with up to 4 students.

The measurements were made in accordance with the AS/NZS1269 “Occupational Noise Management” standards, and noise levels were recorded in both A-weighted [dB(A)] and C-weighted [dB(C)] scales.

Participants

The study involved three music teachers and 40 students, all of whom volunteered to participate. No specific limitations were imposed on the participants in terms of age, gender, or hearing level. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study and the measurement procedures, and they were assured that their involvement would remain anonymous.

The teachers were exposed to high noise levels for extended periods, while students participated in either group lessons or one-on-one practice sessions. The noise levels were recorded during both group activities and individual practice, to assess the variance in exposure based on the type of activity.

Students were also surveyed about their use of personal listening devices outside the classroom. This additional data helped quantify the total noise exposure for students and provided a broader understanding of their overall exposure to high noise levels.

Risk Criteria

In Australia, the Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) regulations govern maximum allowable noise exposure levels for workers. The Australian Standard AS/NZS 1269.4:2005 specifies a daily exposure limit of 85 dB(A) for an 8-hour period.

Instrumentation

Noise exposure was measured using a B&K Model 2231 Modular Precision Sound Level Meter, following the guidelines outlined in the Australian Standard AS/NZS 1269.4:2005.

Results

Part 1 – Sound Level Readings

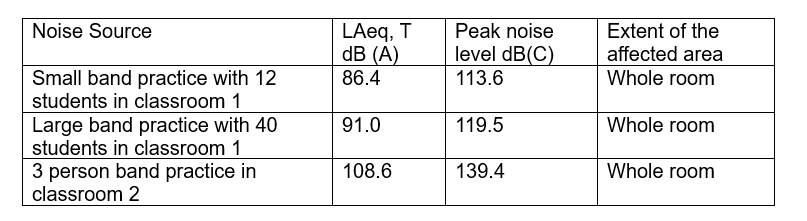

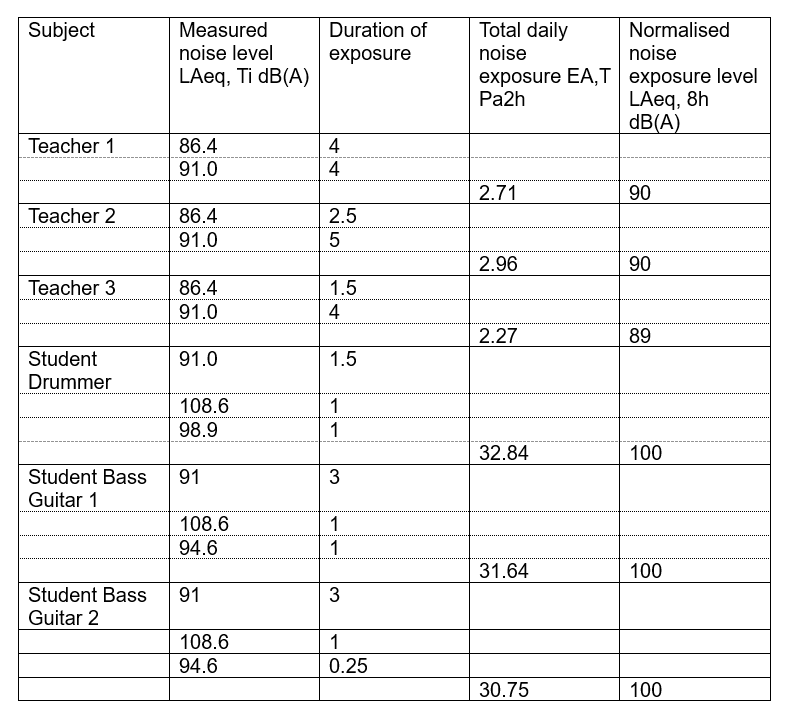

Table 1 – LAeq,T dB(A), peak noise level dB(C) and extent of affected area

Table 2 – Evaluation of Normalised Daily Noise Exposure

Table 1 shows the measured Leq, the measurement duration, dB(A) and dB(C) and the extent of the affected area.

Table 2 shows the measured Leq, Ti dB(A), and the calculated 8 hour Leq. 8h dB(A).

The results of the study revealed that noise levels in the classrooms frequently exceeded the recommended threshold of LAeq 85 dB(A), a level recognized as potentially harmful over prolonged periods. All three teachers were exposed to noise levels above this threshold throughout their lessons.

Noise levels in classroom 2, had peak noise levels that exceeded 130 dB(C), significantly increasing the risk of hearing damage.

The survey also revealed that many students used personal listening devices outside the classroom at unsafe volume levels. This practice significantly increased their overall noise exposure, with several students reporting daily use of these devices for extended periods. The combined exposure from both classroom noise and personal listening devices placed students at a heightened risk of NIHL.

Physical Environment

These classrooms are situated on the ground floor in a dedicated music building, isolated from general teaching areas. However, the design and material choices significantly contribute to elevated noise levels and prolonged reverberation, posing challenges for effective noise control and safe occupational exposure.

There was no acoustic panelling in either room. The walls were made of brick, and both rooms had large windows. The floor of most rooms was covered with carpet tiles.

With the exception of the flooring, all surfaces were mostly reflective.

- Classroom 1:

- Dimensions: 9.5 m x 9.5 m x 2.9 m.

- Construction: Brick walls with glass windows along two sides, mineral fibre ceiling, and carpet tile flooring.

- Acoustics: The hard surfaces of the walls and windows contribute to sound reflection, increasing reverberation and overall noise levels.

- Reverberation time 1.0 seconds.

- Classroom 2:

- Dimensions: 3.8 m x 3.7 m x 3.0 m.

- Construction: Two-way glass on both sides, mineral fibre ceiling, and carpet tile flooring.

- Acoustics: The two-way glass design creates a highly reverberant environment, amplifying sound levels.

- Reverberation time 0.9 seconds.

Number of Students

The effect of the number of students on noise exposure was analyzed by comparing the Leq of classes with the same activity taught by the same teacher, in the same classroom, as shown in Table 1.

The time period the students are in this environment exceeds 85dB(A), it does not exceed the recommended levels of LAeq, 8h dB(A).

However, there are other factors that also influence the overall noise exposure level for students. Some of these factors may be the kind of music being played, whether the students were learning or performing, the duration of the time while performing and listening to examples showed by the teacher, and music listening habits outside the classroom as mentioned below.

Part 2 – Student perspectives on music volume in the classroom and personal listening devices.

Summary of Student Questionnaire Responses

A survey was conducted to assess students’ listening habits and their perception of noise levels in the music classroom. The responses provided insight into their exposure to potentially hazardous sound levels; however, limitations in the survey design, including a small sample size and potential response bias, should be considered when interpreting the findings.

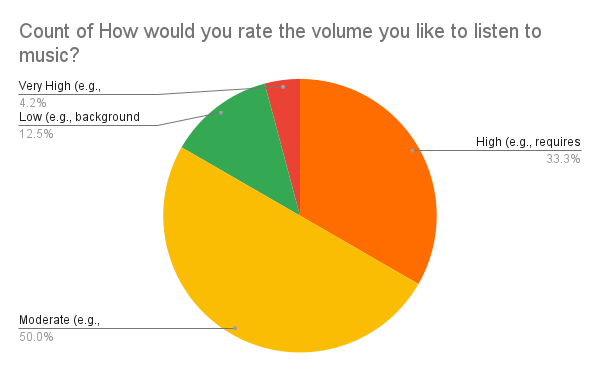

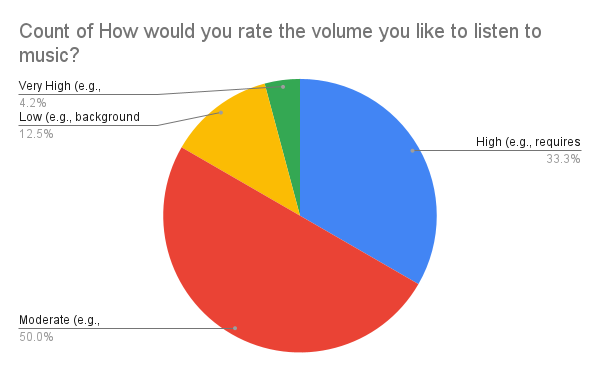

Preferred Volume for Personal Music Listening

When asked about their preferred volume for listening to personal music, the majority of students (50%) reported listening at a moderate volume, while 33.3% preferred a high volume. A smaller proportion of students (4.2%) indicated that they listen at a very high volume, whereas 12.5% reported listening at a low volume. These results suggest that a significant portion of students may be exposed to sound levels that could contribute to long-term hearing risk.

Figure 1: Student preferences for music volume

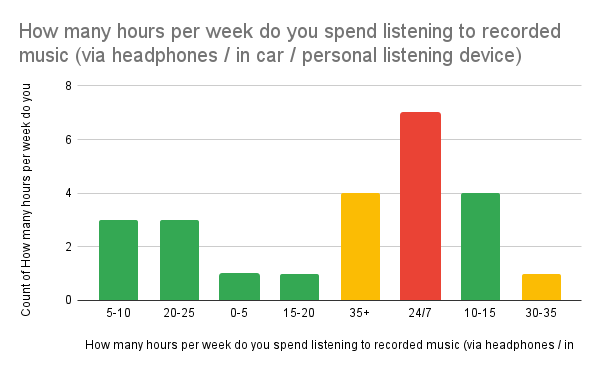

Duration of Personal Music Listening

Students were also asked about their weekly time spent listening to music through personal devices, including headphones and in-car audio. Responses varied widely, with three students reporting 5–10 hours of listening per week, seven students listening for 20–25 hours, and four students exceeding 35 hours per week. Additionally, responses included one student reporting 0–5 hours, another at 15–20 hours, four at 10–15 hours, and one at 30–35 hours. The variation in responses highlights diverse listening habits, with a substantial proportion of students engaging in prolonged music exposure, potentially increasing their risk of noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL).

Figure 2: Student estimate of listening to personal listening devices.

Perceived Noise Levels in Music Classrooms

When asked to rate the noise levels in their music classes, student perceptions varied. While 8.3% of respondents classified the noise as very high, 20.8% described it as moderate. Interestingly, only 0.8% rated the noise as high, which may suggest a difference in individual sensitivity to sound or variability in classroom conditions.

Figure 3: Student perspective of music volume in the classroom.

Chart 2:

Discussion

The findings of this study underscore the significant risk posed by prolonged exposure to high noise levels in music classrooms. The elevated noise levels found in both the teachers’ and students’ environments suggest that without proper intervention, both groups may be at risk of NIHL. Teachers, who are exposed to noise for longer durations, are particularly vulnerable, while students face compounded risks due to their use of personal listening devices.

Limitations of the Survey

It is important to acknowledge certain limitations in the survey methodology. The sample size was relatively small, which may affect the generalizability of the findings.

Additionally, self-reported data can be influenced by recall bias or individual perception differences, particularly in rating subjective experiences such as noise levels. A more structured and standardized assessment of students’ actual noise exposure, combined with objective noise level measurements, would provide a more accurate representation of potential hearing risks.

Despite these limitations, the responses highlight that many students frequently engage in prolonged listening at high volumes and perceive their classroom environments as moderately to very noisy. These findings underscore the need for further research and potential interventions to promote safer listening habits and hearing conservation strategies among students.

Recommendations

Given these results, it is critical to implement strategies that mitigate noise exposure in music education settings. This includes the introduction of monitoring music levels within the classroom, and hearing protection during high-noise activities. Additionally, educational programs should be introduced to teach both teachers and students about the risks of noise exposure and the importance of safe listening practices.

For students, this may include the promotion of lower volume settings on personal listening devices and the implementation of “quiet time” in the classroom to reduce noise exposure.

Engineering Noise Controls

- Immediate Recommendations

- The drum kit poses a serious risk of hearing loss with peak noise levels of 139dB (C), requiring immediate noise reduction measures such as drum pads or low-volume drum heads. Additionally, the bass guitar significantly contributes to classroom noise exposure and should be controlled through volume-limiting devices or amplifier adjustments.

- Hearing Protection Requirement:

- Install signage stating: “Hearing protection must be worn when entering Classroom 2 if drums or electric guitars are in use.”

- This ensures awareness of the high-reverberation environment and promotes safe practices.

- Noise Monitoring System:

- Traffic Light Noise Monitoring System:

-

- Install a traffic light Sound Level Meter system to visually alert occupants when sound levels exceed 85 dB(A). This encourages self-monitoring of noise levels during use.

- Acoustic Treatment:

In Classroom 2, due to its higher noise levels, we recommend implementing acoustic treatment such as wall and ceiling sound absorption panels. This will reduce reverberation and lower the overall noise exposure.

In Classroom 2, due to its higher noise levels, we recommend implementing acoustic treatment such as wall and ceiling sound absorption panels. This will reduce reverberation and lower the overall noise exposure.

Classroom 1 should also be treated with acoustic panels, though it remains a secondary priority due to relatively lower noise levels compared to Classroom 2.

- Long-Term Solutions

Enhanced Acoustic Panels such as Durra Panels or Mass Loaded Vinyl

Bass Traps in the corners to absorb low frequency sound.

- Teacher-Specific Risks

Teachers are exposed to both vocal strain and high noise levels. We recommend the use of amplification devices, such as microphones and speaker systems, to reduce the need for vocal projection and decrease the strain on their voices.

- Follow-Up Noise Assessment

A follow-up noise assessment should be scheduled 6 months after the implementation of acoustic treatments to evaluate the effectiveness of the changes and confirm whether further measures are needed.

Hearing Conservation Program

To reduce exposure to harmful noise levels, one effective strategy is the implementation of a hearing conservation program. This program serves as an administrative guideline aimed at protecting individuals who are regularly exposed to high noise levels.

- Hearing Protection:

Signage should be installed in both classrooms to mandate the use of hearing protection during noisy activities. Teachers and students should be provided with suitable hearing protection devices, including earplugs or earmuffs, to be worn whenever noise levels exceed 85 dB(A).

Introducing hearing protection devices, such as “musician earplugs,” which offer a flat frequency response to preserve sound quality while still providing adequate noise attenuation. Users should be trained on the proper usage, fitting, and maintenance of these earplugs. The exact recommendations were included in the full report.

- Hearing Health Surveillance

Under the Work Health and Safety Act and Regulations 2012 (South Australia), businesses must provide audiometric testing for employees who are regularly exposed to noise levels above the recommended exposure standard (85 dB(A)).

To proactively protect teachers and students hearing, we propose the initiation of a hearing surveillance program including Otoacoustic Emissions (OAE) testing. OAE testing can detect early changes in Outer Hair Cells (OHC) before traditional audiometric thresholds are affected.

All staff members should undergo hearing assessments (audiograms, high-frequency audiograms, and otoacoustic emissions) within the first three months of their employment.

Ongoing Testing:

Hearing assessments should be conducted every two years thereafter.

- Educational Program on Safe Listening Practices into the curriculum:

Students should be educated on the importance of safe listening, including understanding the risks of loud sounds and the role of hearing protection.

The Hearing Health Program includes two key components:

(1) establishing protocols to minimize the risk of hearing damage and

(2) defining roles and responsibilities within the program. Some essential elements of the program are:

- Educating individuals about the dangers of excessive noise exposure and the associated risk of hearing loss.

- Conducting regular audiometric screenings, ideally every two years, to monitor hearing health. These screenings typically involve pure-tone air conduction tests, which are simpler and less diagnostic than more advanced hearing assessments, but still provide valuable insights into the effects of noise exposure on hearing.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this study, the following conclusions can be made:

- Music teachers are exposed to sound levels that exceed the recommended 85 dBA limit during their teaching sessions (LAeq values surpass the threshold).

- Music teachers face a potential risk of hearing loss due to their exposure to high noise levels, and it is recommended that measures be taken to reduce this exposure.

- Student listening habits highlight a concerning trend of prolonged exposure to potentially harmful sound levels. A significant portion of students reported listening to personal music devices at high or very high volumes, with some exceeding 35 hours of weekly exposure.

- Perceptions of noise levels in the music classroom varied, with some students indicating that they experience high sound levels during lessons. These behaviours place students at an increased risk of developing noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) over time.

Given these patterns, an education program is essential to raise awareness about safe listening practices and the long-term consequences of excessive noise exposure. Such a program should inform students about safe volume levels, the dangers of prolonged headphone use, and the cumulative impact of both classroom and recreational noise exposure. By equipping students with this knowledge, they can make informed choices to protect their hearing health and minimize the risk of permanent damage.

It is essential that schools take immediate steps to reduce noise exposure, not only to protect hearing but to ensure that future generations of teachers and students can continue to enjoy and participate in music without the threat of hearing loss.

References

AS/NZS 1269:2005 (Occupational noise management)

Behar, A. et al. (2004) ‘Noise exposure of Music Teachers’, Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 1(4), pp. 243–247. doi:10.1080/15459620490432178.

Maffei, L., Iannace, G. and Masullo, M. (2011) ‘Noise exposure of physical education and Music Teachers’, Noise Notes, 10(4), pp. 41–50. doi:10.1260/1475-4738.10.4.41.